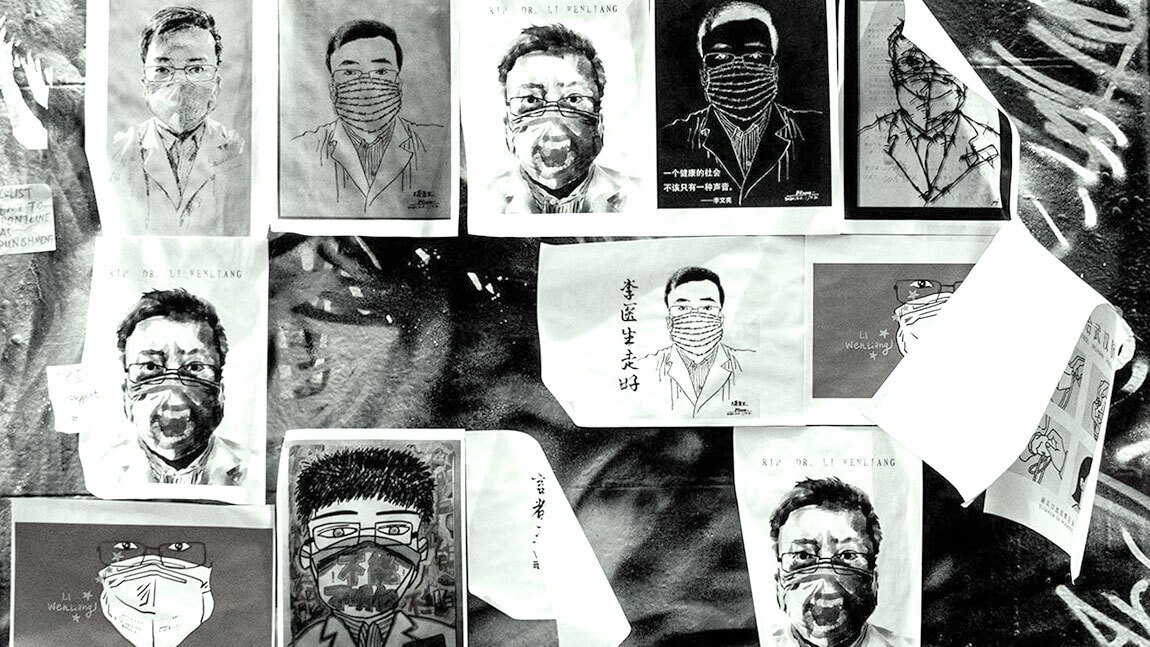

“Rest in Peace” posters of Dr. Li Wenliang, who warned authorities about the coronavirus outbreak, seen at Hosier Lane in Melbourne, Australia; by Adli Wahid.

Until the Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1912), Japan would have been defined by words like samurai, kimono, geisha, and others associated with its folklore. Japan’s industrial revolution opened space for a new world and word: modern. However, Japanese modernity only became memorable when associated with brands like Hitachi (1910), Panasonic (1918), Fujifilm (1934), Toyota (1937), Sony (1946), and Sony’s Walkman (1979) among many others.

The unspoken truth, however, is that the Meiji era held a powerful metaphor — the era of light. Meiji means “Enlightened Rule”, a construct that lent itself to a deliberate, state-led industrialization policy. A reenergized “brand Japan” enabled the development of new commercial brands, just as much as the latter helped validate the metaphor Japan came to represent, in a mutually reinforcing relationship.

These metaphors represent the mental associations and constructs we create when thinking of those nations just as much as how their inhabitants may see themselves; these are their place brands. Speaking with Professor Sohail Inayatullah, UNESCO’s Chair in Future Studies, who recently worked on the education futures of China, he said that metaphors present themselves as the main causation drivers of the future.

Metaphors like Hippocrates’ “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”, or Shakespeare’s “Clothes maketh the man” are just as powerful to informing our sense of self as the more modern “I buy, therefore, I am”. In fact, even the briefest exposure to the Apple logo can make you behave more creatively, according to research led by Professor Gavan Fitzsimons from Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. In this case, the apple on Apple’s logo is a metaphor for creativity or, as stated on the brand’s slogan, “think different”. The transformational power of metaphors (or brands) goes even further. Cardiologist and author Sandeep Jauhar explains, during the TEDSummit 2019, that our emotions impact the health of our hearts — causing them to change shape in response to grief or fear, to literally break in response to emotional heartbreak — demonstrating the impact of what is metaphorically felt over a very tangible reality.

When considering the world’s geopolitical volatility and the ongoing pandemic, protecting the way others feel about your nation — especially for brand China — has never been so important. And investing in a nation’s brand appeal pays back. For instance, back in 2012, Mexico’s President Felipe Calderon hired nation-branding expert Simon Anholt, for strategic advice in order to improve the nation’s image. By 2019, Mexico became America’s top trading partner.

Nation-branding goes beyond just telling your country’s story well, as China’s propaganda apparatus has been doing for a while now; it’s about crafting a narrative that reshapes reality.

Soft power with hard metrics is a means, not an end

While the virus is the real issue, the Chinese government’s naive attempt at protecting its image through poor conduct in communicating and responding to the disease was what ignited mistrust, commercial slowdown, and cases of racism worldwide.

Marco Wong, a local councilor in the Tuscan town of Prato, home to a large Chinese population, told The Guardian: “Parents aren’t sending their children to school if there are Chinese classmates and people are writing on the internet not to go to Chinese shops and restaurants.”

This is more than just a disease. It tests a society’s health systems, its government, politicians, the economy, and above all things, the soft power of their nations. For China, the opportunity is to re-engineer its perception by departing from the factory metaphor and reframe its soft power.

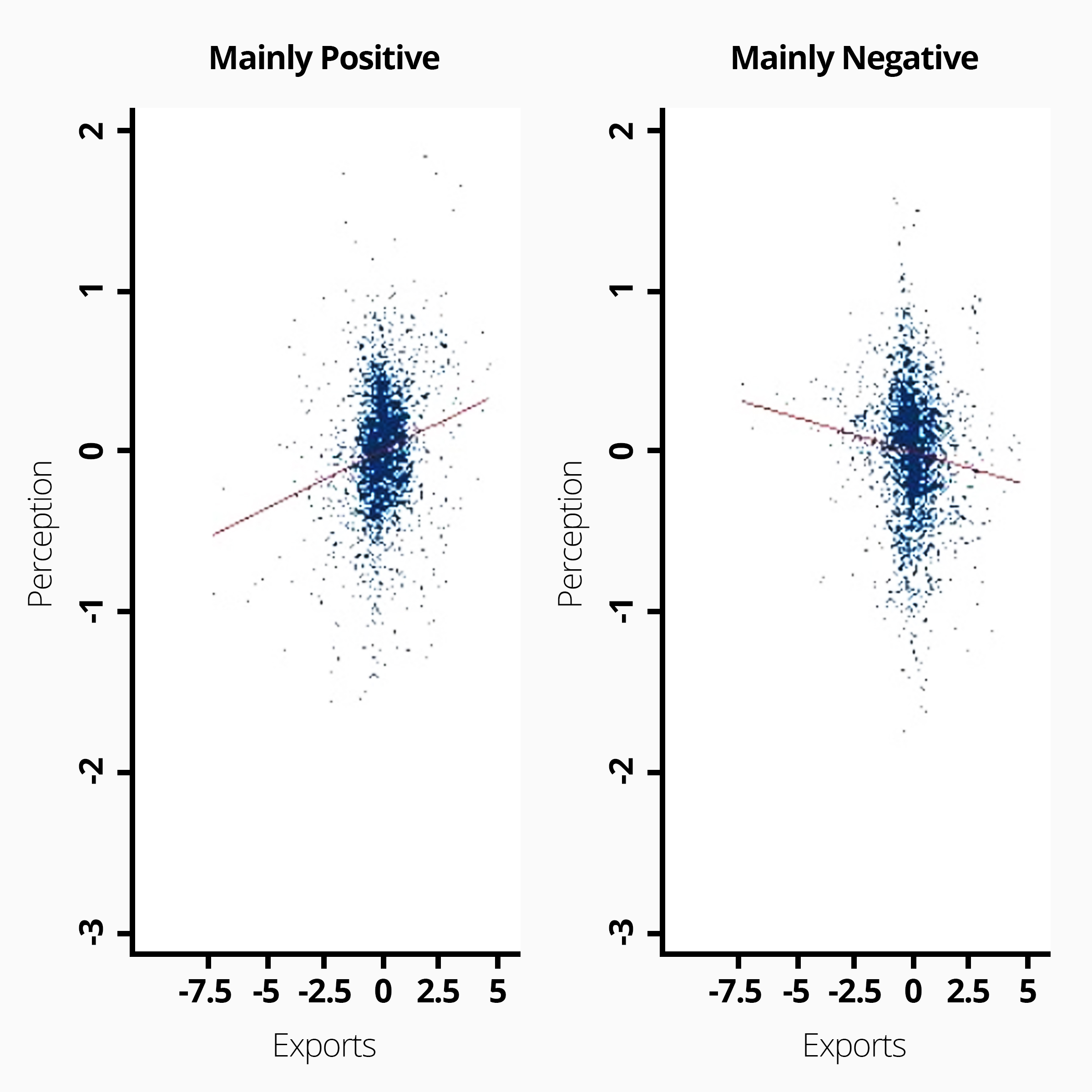

Soft power was defined by political scientist Joseph Nye as being a country’s ability to attract or persuade others to do its bidding, without having to resort to any form of coercion. As demonstrated by the University of California, Berkeley, soft power matters because countries that score high on cultural attractiveness export more. Every 1% net increase in soft power raises exports by around 0.8%.

Source: Like Me, Buy Me: The Effect of Soft Power on Exports; Centre for Economic Policy Research

In 2016, according to the Soft Power Today study, such a rise would have been worth £1.3bn for the UK, which recorded £197bn of foreign investment. While brand China may have considerably eroded its trustworthiness with a weak PR effort, its soft power was put to use to minimize the collateral effects from the pandemic and garner support from neighboring countries.

At one meeting, ASEAN foreign ministers joined hands with Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and shouted “Stay strong, Wuhan!” Stay strong, China! Stay strong, ASEAN!” Yet, nothing fuels and validates a nation-brand like the relationship between place and production.

Just like the symbiotic relationship between Meiji’s Japan and its subsequent “enlightened” tech brands, China has also made a tremendous effort to launching and sustaining successful global brands, even in spite of the heated trade war with the USA. Sportswear company Li Ning’s debut at NYFW and JD.com’s Nasdaq success story speak directly to that.

Nonetheless, brand China needs to be stronger than the summation of its commercial brands, turning “made in China” into a magnet for more positive exchanges and keeping its influence as strong as before the outbreak.

Chasing the “Chinese Dream” metaphor

According to Brand Finance’s CEO David Haigh, in relation to the 2019 Nation Brands study, “China is undergoing a meteoric rise on the global stage, rivaling the traditional nation brand powerhouses in the West. Despite economic and political challenges, China’s nation brand value has grown by 40% reaching $19.5 trillion, consistently outpacing the US and other major economies.”

But that was then. According to Hoover Institution Fellow Victor Davis Hanson, [China] “ruined their international brand,” having potential serious repercussions on its economy as foreign companies may exit. During an interview on live TV, Hanson added: “You think if you’re Italy or Switzerland or Germany or Australia, you really want to have your antibiotics produced in China when this is all over? If you’re a tourist and you went to China and somebody said there’s a virus contained but don’t worry, it’s contained — would you believe that?”

Commerce, not geopolitics or policymaking, is the path to prosperity and peace. It is the only space where our perpetual state of disagreement is settled through the voluntary exchange of goods and services. An empirical study published in the Review of Development Economics Journal confirmed that, as bilateral trade interdependence increases, so does the peace process.

In the case of brand China, the current strategy — encompassing an annual Chinese Brands Day every May 10th, and a nationwide China Council for Brand Development — is no longer enough. To heal the nation’s perception and sustain its role in our globalized economy, brand China needs to fix the problems it created. In the UK, for instance, several companies are retooling themselves to fight the pandemic and confer a leadership status to their nation of origin through this crisis.

Above and beyond, such initiatives reenergize the perception of British ingenuity that skyrocketed from the 19th century Manchester and was sustained by several other inventions like the ATM (1967), the World Wide Web (1989), Dolly, the First Mammal Clone (1996), and many others. These efforts, combined, should help provide plenty of soft power value and the genesis of what could be an entirely new business ecosystem; despite the UK Government’s questionable herd immunity strategy.

Precise orchestration of marketing, media, and branding tactics are needed for a meaningful, new narrative. In the case of China, having strong, global brands is not enough. Collectively, they must mean something more than their singular narratives. There’s no better time than now, there’s no better enemy for a heroic China than a virus. From unsettling “Chinese Whispers” to the “Chinese Dream”, a new metaphor able to infuse new meaning to its economy, is the nation brand’s imperative for future prosperity in the 21st century.

Cover image source: Adli Wahid

*By Sérgio Brodsky, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.